Activity Analysis and Functional Cognition

Jan 06, 2025

Activity analysis is one of the most powerful tools occupational therapists have for understanding and addressing cognition in functional peroformance. It offers a structured way to break down the steps, demands, and environments involved in a task, allowing practitioners to assess not only the physical aspects but also the cognitive and psychosocial components. This holistic approach ensures that interventions are comprehensive, targeting the full scope of a client’s needs to promote engagement, independence, and overall well-being.

Activity Analysis as a Core Tool for Functional Performance

At its core, activity analysis allows therapists to dissect everyday tasks into their smallest components. By doing so, they can assess how different performance skills—such as motor coordination, sensory processing, and emotional regulation—intertwine to complete an activity successfully. This method exposes hidden barriers that may not be immediately apparent during a general observation of function. For example, analyzing meal preparation can reveal underlying deficits in motor planning, sequencing, or attention, guiding targeted interventions that foster improved performance and safety.

Functional Cognition in Occupational Performance

Cognitive processes extend far beyond executive functions like planning and problem-solving. Memory, attention, perception, spatial awareness, and sensory integration all play critical roles in how individuals interact with their environment. Activity analysis highlights how these processes affect performance during tasks, revealing both strengths and areas for intervention.

Example: Consider the task of managing medication. Through activity analysis, a therapist may observe that while a client successfully recalls the medication schedule (memory), they struggle with organizing pill containers (spatial awareness) or recognizing different medications (visual perception). Addressing these specific deficits through compensatory strategies or task adaptation ensures more accurate, functional solutions that extend beyond executive function remediation.

Neuroscience-Informed Care in Treatment Planning

Neuroscience-informed care, when combined with activity analysis, strengthens treatment planning by addressing both motor and cognitive components of function. This approach leverages the principles of neuroplasticity, allowing therapists to create interventions that promote both physical and cognitive rehabilitation through structured, meaningful activities.

Case Example: A client recovering from a stroke exhibits challenges in upper body dressing. While muscle weakness is apparent, activity analysis reveals additional deficits in proprioception, body schema awareness, and sequencing. A neuroscience-informed intervention might incorporate mirror therapy to activate mirror neurons for motor recovery, while also including task-based cognitive exercises to improve spatial awareness and memory for dressing routines. This dual-focus intervention ensures that therapy targets the root of performance deficits across domains.

Applying Functional Cognition to ADLs and IADLs Through Activity Analysis

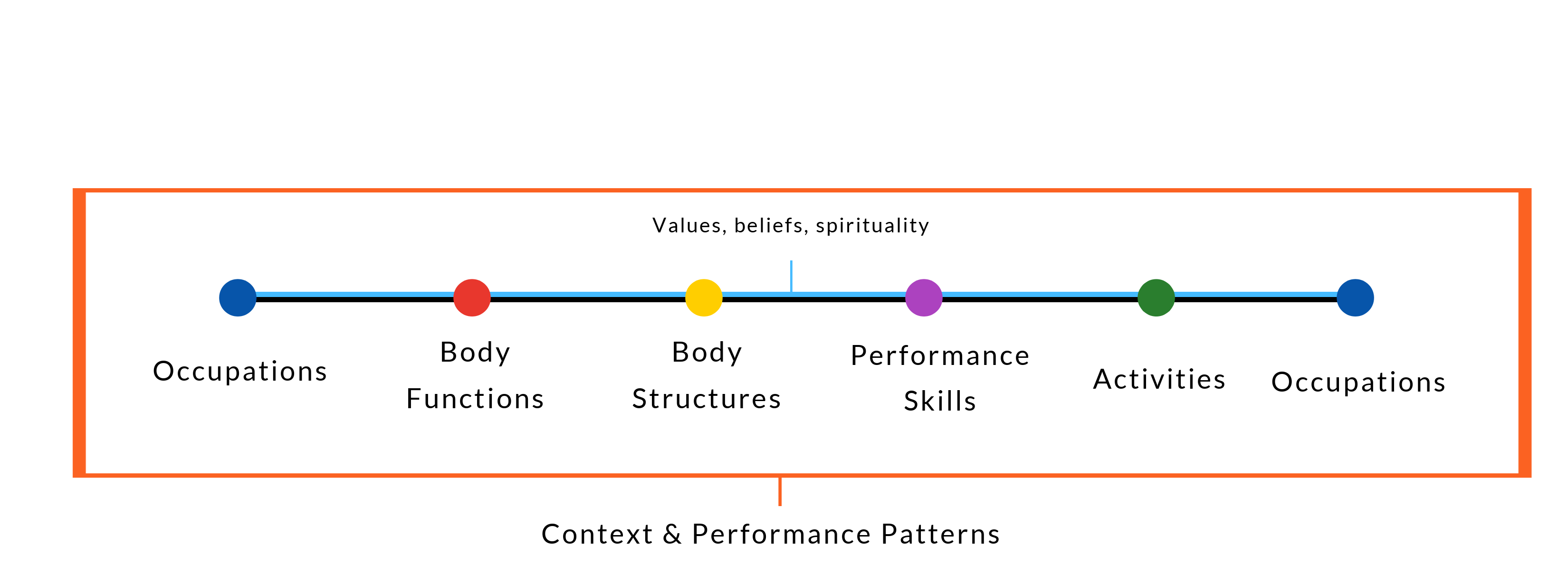

Applying functional cognition to ADLs (Activities of Daily Living) and IADLs (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) requires a step-by-step breakdown that considers the entire occupational therapy framework. This method integrates not only motor and cognitive components but also personal values, beliefs, spirituality, and the influence of environmental context.

Example – Meal Preparation (IADL)

Step 1: Define the Occupation

Occupation: Preparing a meal for oneself or family.

- This task may reflect personal roles (e.g., caregiver), routines (e.g., making dinner nightly), and rituals (e.g., cultural or spiritual meal preparation).

- Context: The kitchen environment, available tools, time of day, family involvement, and emotional ties to meal preparation.

Step 2: Identify Body Functions

Body Functions Involved:

- Cognitive: Working memory, sustained attention, sequencing, and problem-solving.

- Sensory: Visual perception, tactile input, olfactory sense for monitoring food readiness.

- Motor: Fine and gross motor coordination, bilateral integration, and postural control.

- Emotional: Emotional regulation during stressful or multi-step tasks.

Step 3: Address Body Structures

Body Structures Relevant to the Task:

- Nervous System: Structures related to motor planning, executive function, and sensory processing.

- Musculoskeletal System: Upper extremity strength, range of motion (ROM), and endurance.

- Digestive and Respiratory Systems: Impacting energy levels and overall physical stamina during task completion.

Step 4: Performance Skills Breakdown

Performance Skills Required:

- Motor Skills: Reaching for ingredients, chopping vegetables, stirring pots.

- Process Skills: Sequencing tasks, timing each cooking process, and adjusting for missing ingredients.

- Social Interaction Skills: Engaging with family members or guests during meal preparation.

Step 5: Activity Breakdown (3+ Performance Skills Per Activity)

Activity: Chopping vegetables

- Motor Skills: Grasping the knife, applying appropriate pressure, coordinated slicing.

- Process Skills: Recognizing vegetable types, organizing cut pieces, and correcting errors (e.g., re-cutting uneven pieces).

- Cognitive Skills: Sustained attention to the task, visuospatial processing for knife positioning, and abstract thinking when substituting ingredients.

Activity: Boiling pasta

- Motor Skills: Lifting pots, pouring water, stirring pasta.

- Process Skills: Timing water boil, adding pasta, and ensuring even cooking.

- Cognitive Skills: Memory (recalling pasta cook time), attention-shifting (watching stove while prepping sauce), and decision-making if the pasta overcooks.

Step 6: Occupation Breakdown (2+ Activities Within Context)

Occupation: Full Meal Preparation

- Combines activities such as chopping, boiling, sautéing, and plating food.

- Requires integration of performance skills across multiple domains (motor, process, cognitive).

- Affected by roles (parent, host), routines (daily dinner preparation), and spirituality (cooking as a family tradition or religious practice)

Enhancing Clinical Practice

Cognitive Remedial Therapy

Engaging in full activity analysis allows occupational therapists to design interventions that not only reduce cognitive load but also remediate underlying deficits through targeted, task-based activities. This dual approach strengthens cognitive endurance, enhances motor-cognitive integration, and promotes greater functional performance.

Examples of Remedial Approaches:

- Motor-Cognitive Dual Tasking: Incorporating activities like balancing while sorting visual stimuli or walking while recalling sequences to improve divided attention, executive function, and working memory.

- Progressive Overload for Cognitive Endurance: Designing graded activities (e.g., progressively increasing steps in a cooking task) to challenge attention span, task persistence, and cognitive flexibility over time.

- Task Variation to Reduce Cognitive Rigidity: Rotating motor-based cognitive tasks (such as alternating between fine and gross motor activities) fosters cognitive flexibility and adaptability in response to task demands.

- Error Augmentation: Deliberately introducing controlled errors into tasks (e.g., placing the wrong ingredient) to build error detection, correction, and problem-solving skills.

Cognitive Compensation Strategies

Alongside remediation, cognitive compensation strategies help clients manage tasks more efficiently by reducing unnecessary cognitive demands, thus allowing bandwidth for higher-order thinking and physical performance.

Examples of Compensation Strategies:

- Visual Checklists and Timers: Free up working memory by externally managing multi-step processes, improving focus and precision.

- Task Simplification and Environmental Modification: Pre-organizing materials and tools to reduce sequencing demands, allowing clients to concentrate on fine motor tasks.

- Routine Development for Error Prevention: Routines decrease decision fatigue, promoting smoother task completion and reducing the likelihood of errors.

- Dual Task Management: Use verbal rehearsal or mental imagery alongside physical tasks to train divided attention without overloading the client.

A Balanced Approach: Remediation and Compensation

By integrating both remediation and compensation into practice, occupational therapists empower clients to build lasting cognitive endurance while maintaining success in everyday tasks. This holistic approach fosters long-term functional independence and enhances the overall quality of life.